May is pine pollen time at Kew Gardens and today I spent a fun hour or so taking pictures of different pine species and their pollen cones (and a few non-Pinus ring-ins). For the extreme pine nerds among you!

May is pine pollen time at Kew Gardens and today I spent a fun hour or so taking pictures of different pine species and their pollen cones (and a few non-Pinus ring-ins). For the extreme pine nerds among you!

Spring has sprung (finally) in the UK and now is the time that many trees flower, so they can pollinate the next generation with enough time for seeds to develop before winter. Plant reproduction is quite a complicated multi-stage process, but for the purposes of this post it’s enough to know that pollen is the vehicle for the male gamete (the plant equivalent of sperm). It is produced by anthers in angiosperms (flowering plants) and by male cones in gymnosperms (including conifers).

It turns out that pollen production can happen in different places. In some trees, both male and female parts are within the same flower (known as ‘perfect’ or ‘complete’ flowers). In others, they are separate flowers or cones on different parts of the same branch, shoot or tree – known as monoecious trees. In yet others they are separate flowers or cones on single-sex trees – known as dioecious.ref

Whilst female flowers/cones and the fruit associated with them are usually obvious, the pollen-bearing male flowers/cones are often hard to spot and sometimes people don’t even realise they are there (it was only about 2 years ago that I realised that oak trees even had flowers!). After releasing their pollen, male reproductive parts usually drop off and disappear from view, while the female flower/fruit/cone persists as the seeds develop. So it’s definitely worth appreciating male tree flowers when you see them, as they don’t hang around for long.

In angiosperms, many male tree flowers take the form of catkins. A catkin is an “elongated cluster of single-sex flowers bearing scaly bracts and usually lacking petals.”ref Male catkins appear on oak, chestnut, alder, birch, hazel, poplar, aspen, hornbeam, walnut and willow – a good overview of these is on the UK Tree Guide website and some examples are shown below. There are female catkins as well, but these don’t contain pollen, which is one way to tell them apart.

Some trees have flowers that look more like what we learn about at school, so-called ‘perfect’ flowers, with both male and female parts. Examples of trees with this type of flower structure include maples, hawthorn, lime, horse chestnut and many fruit trees including apple, cherry, pear and plum (see below).

Gymnosperms do not have flowers at all, instead they have male and female cones (also called strobili). 98% of gymnosperms use the wind for pollination, with the male pollen cones releasing their pollen into the wind to find its way to females.ref Because this is a bit of a hit and miss approach, gymnosperms produce a *lot* of pollen – one study estimated Juniper pollen production to be up to 532 billion pollen grains per tree!ref These vast quantities of pollen create pollen clouds, which you can see in a video on youtube here.

Another nifty thing is that female conifer cones produce a ‘pollination drop’ – this is a drop of liquid which sits on the surface of the cone to catch wind-borne pollen. As soon as pollination takes place, the drop is quickly retracted back into the cone.ref And you’ll notice that often male pollen cones are positioned at the top of a tree and in open positions along the stem (ie. not covered by leaves), to give their pollen the best chance of going far and wide.ref

Male cones on gymnosperms are smaller and less conspicuous than females, but, I think they’re still beautiful and worthy of our appreciation. Here are some examples of gymnosperm male cones:

Conifer species which have leaflets have a sort of tree-within-a-tree approach – such as the cypress below. – it has browny-pink male pollen cones on the ends of the shoots towards the back of the leaflet, and green developing female cones on the ends of the shoots at the tip of the leaflet.

There are more great images including scanning electron microscope images of gymnosperm pollen in this research paper.

But what if the trees in your bonsai collection don’t have any flowers or cones at all? Unfortunately this is a sign that they haven’t yet reached their reproductive phase. It’s hypothesised that a plant’s transition to its reproductive phase happens after a certain number of cell divisions have taken place.ref If you keep pruning the new growth off, your tree may never reach a reproductive phase, since it may never achieve the number of cell divisions required. The only way around this is to let your tree grow, use a mature tree to begin with, or use grafted material which comes from mature trees.

In the meantime, make sure to take a good look at your trees and the trees around you, and appreciate the underrated male tree flowers when they make an appearance.

The reproductive system and organs of plants are extremely varied and complex, and worthy of an entire website to themselves – a comprehensive view is beyond the scope of this website. But what I want to do is provide a bit of information to help you identify which buds might be reproductive vs vegetative.

There are different buds for vegetative (shoots & leaves) and reproductive (flowers, strobili) organs – within each bud a different set of components develop depending on what kind of bud it is. For angiosperms, it’s hypothesised that flower buds are based on the same structures as vegetative buds – that is, a bud starts as vegetative and then differentiates into a flower bud.ref For gymnosperms, reproductive buds contain male or female strobili.ref These are the male pollen cones or the female seed cones.

There are two ways to work out which bud is which – by their appearance or by their position on the tree. The appearance route is best aided by dissecting some actual buds from the tree you are interested in, so you have real data from the real tree. Otherwise, read on for more information about how vegetative and flower buds differ in appearance.

Vegetative buds are “encased by strong, coarse, mature scale leaves. Thinner, more membranous scale leaves make up the next layer. The scale leaves form a protective enclosure surrounding the developing foliage leaves.”ref In many of the articles online, leaf buds are said to be thinner than flower buds (at least for angiosperms). Below are the vegetative buds of Acer pseudoplatanus and Fraxinus excelsiorref:

A flower bud develops sepals, petals, stamen, pistil, ovaries & anthers, instead of leaves and more buds. Below is a scanning electron micrograph of a Bing cherry flower bud forming where M is the meristem, B is the bract and F is the very start of the flower forming – the progression over time is from left to right. On the right is the pistil with ovary (O) style (SY) and stigma (SM). The scale of the image is provided by the white bar on the bottom right hand side, which is 100 micrometres (or microns) – about 1/100th of a centimetre. Obviously it’s impossible to detect a flower bud at this stage by eye, it’s way too small!

The buds of these Bing cherries started forming and were detectable under a microscope from mid-May (the location was Washington state USA) – the year before they would flower and fruit. At a lower magnification below is a progression in flower bud development of a Camellia – the key difference is that at A2 when the flower starts to differentiate, the tip of the bud becomes more rounded and flattens.

Some of the trees we use in bonsai are dioecious which means they are only male or female and not bothref. This means they will produce only one type of flower or strobili bud. To check whether your gymnosperm is dioecious or monoecious you can check the gymnosperm database. Unfortunately I don’t have a reference link for angiosperms.

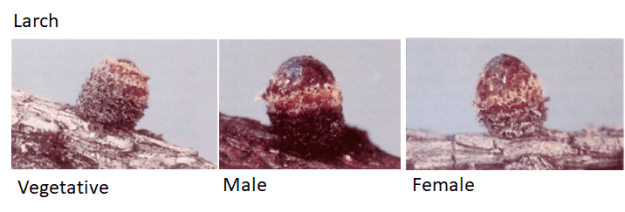

In gymnosperms there are no flowers, instead the reproductive organs are male or female strobili (pollen or seed cones respectively). A brilliant reference for some of these is available online here. An extract from the publication is provided below with some examples of vegetative and male & female strobili buds.

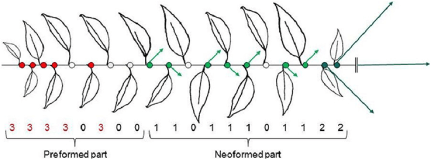

As noted another way to determine the type of bud is by its position. To do this you need to work out what the architecture of your tree is and where buds of different types typically form. Trees conform to one of 24 architectures as described in Tree Architectural Models and these give an indication to the location of reproductive buds. Trees can have one model for their juvenile phase (before they flower or adopt mature foliage) and then one for their reproductive phase.

In the case of apple, it has been found to conform to Rauh’s model when juvenile and Scarrone’s when reproductive.ref Even with this, “great differences exist between cultivars whether they belong to “spur” vs. “spreading” or “terminal bearing” growth habit”ref

In cherry, “The long branches bear short shoots, also called spurs, in lateral positions on the distal half or two thirds of the branch with more vigorous spurs toward the distal part [the most distant part]. Flowering occurs in axillary positions on the five to six basal-most nodes of all shoots whether long or short. Floral buds are thus located exclusively on the preformed nodes of the previous year shoots.”ref

In some species, particularly pines, the long shoot buds have many different components on them in a specific order. Here is a Pinus contorta bud – you can see the male (pollen) cones appear first, and are positioned at the bottom of the final shoot, and the female (seed) cones appear last just below the top of the shoot.

A similar layout is seen in Pinus thunbergii:

As you can tell from the above, there is quite a bit of complexity in understanding the architectural model of a tree, and where different buds form, as there are many variables involved. Observation is probably going to be the better method.

Related posts: