I live in London, a city sitting on a giant chalk deposit which formed in the Cretaceous period and stretches all the way to France (via the Eurotunnel)ref Chalk is a form of limestone made up of the shells of marine organisms, and is comprised mostly of Calcium Carbonate (CaCO₃).ref According to my water supplier (Thames Water) “When your drinking water seeps through this rock, it collects traces of minerals like magnesium, calcium and potassium. This is what makes it hard.”ref

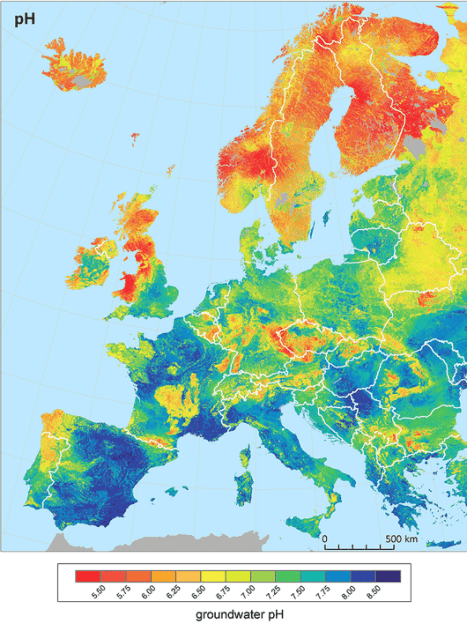

As you can see the water in my area is towards the harder end of hard. But there are plenty of places in Europe with hard water as well, as you can see in this map which comes from a study measuring groundwater in 7,577 sites across the region – most areas in fact are hard with exceptions in Scandinavia, Scotland and northwestern Spain (where igneous/volcanic bedrock dominates)ref:

What is also interesting from this research paper is the corresponding map of groundwater pH (see below). Groundwater pH determines your tap water pH if that’s where your drinking water comes from. Some areas source their drinking water from surface water as well, such as lakes and running watercourses – for example in Sweden it’s 50/50.ref

pH is closely associated with water hardness, with higher levels of calcium carbonate leading to increased pH (in the world of agriculture a common practice to raise the pH of acidic soils is ‘liming’ – or adding calcium carbonate)ref. Look at the areas in Southern Spain and France below which are pH 8 and above – their groundwater is also hard as shown in the map above.

The water in my taps is pH 7.75, so getting close to 8 which is relatively high. Not only that, but continued watering and drying of a bonsai medium with calcium-carbonate-rich water could increase the concentration of calcium carbonate in the pot and potentially make the pH even higher. But is this a bad thing?

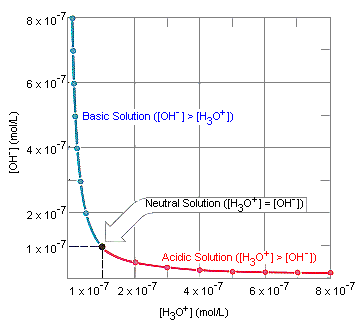

To answer that question we need to take a detour into pH and what it actually means. At this point you can be thankful that usually I wait for a couple of days before posting, because otherwise you’d be deep in the weeds of ions, acids & bases and cursing my lack of editing skills! The (relatively) simple version is that pH is a measure of the concentration of hydronium (H3O+) ions relative to hydroxide (OH–) ions in water. In a neutral solution like pure water, they are at equilibrium and there is the same amount of each. The chart below shows the different ratios of hydronium to hydroxide ions at each pH. You will notice that in the red section there are more hydronium than hydroxide – this is acidic. In the blue section there are more hydroxide and less hydronium – this is alkaline (aka basic).

pH is mainly a useful way of describing a chemical environment, as it helps to explain how other chemicals will react in that environment. For example, when a low pH (acidic) solution reacts with many metals, hydrogen gas and a metal salt are created.

pH is one of the fundamental attributes that affects living things – including plants. In living cells a difference in pH across the cell membrane is harnessed to drive some of the most fundamental processes for life itself – photosynthesis and respiration.ref1, ref2 Living things are generally very good at managing the pH inside their cells and have feedback processes to adjust it up or down according to their needs and the environment (called homeostasis). Studies have shown that pH within plant cells is maintained at a small range of 7.1–7.5.ref

It’s when plant cells interface with the outside world, such as when taking in nutrients from the soil, that pH can make a difference to the efficiency (or not) of these reactions. Nutrients are taken up by plants as ions – ie. dissolved in water. This means that they need to be in solution for root hairs to take them up, and that solution can be acidic, alkaline or neutral.

Dissolved substances in the soil water (which change its pH) can also change the availability of nutrients – for example calcium ions will react with phosphorus ions to make calcium phosphate, so the phosphorus is unavailable for plants.ref But plants adjust their uptake according to these changes, so when they detect pH levels which reduce nutrient availability, in many cases they adjust their uptake to compensate, and these forces work in opposite directions.ref The overall effects of pH on the availability of nutrients to plants are a combination of the effects of pH on absorption by soils and the effects of pH on plant uptake.

Below is a chart showing the absorption of different nutrients by soil (in this case geothite, an iron rich soil). You can see that due to their different chemical makeup, each nutrient has a different absorption rate – the higher the absorption, the less available for plants.

Negatively charged metals (‘anions’) have a more consistent soil absorption profile – and most are absorbed by the soil eventually when the pH is 6 or above. But uptake by plants is significantly increased as pH rises.

So far it seems like acidic soils might provide more nutrients – but also more toxins (eg. cadmium, lead & aluminium). But the release of organic matter, including nitrogen, sulphur and the activity of microbes which perform this breakdown, is increased at higher pH, and the uptake of metals is increased.ref So it’s really a conundrum to work out the net effect of all these interactions! What do we actually know? Some findings include:ref

- Phosphate fertiliser is least effective near pH 7; it is necessary to apply more of it to achieve the same yield as at lower pH. It is most effective near pH 5

- Boron uptake is consistent between pH 4.7 and pH 6.3, but a 2.5-fold decrease occurs at pH 7.4

- Molybdenum uptake is eight time higher at pH 6.6 compared to pH <4.5ref

- Uptake of metal ions from solution by plants is increased by increasing pH – but their availability is decreased. This applies to toxins as well as nutrients. Magnesium and potassium are two important nutrients to which this applies.

- Sulphate’s absorption by soil decreases markedly with increasing pH but plant uptake also decreases – the net effect has not been determined.

There is actually a fantastic diagram which shows the best soil pH range for each plant nutrient – you can see this all over the internet and it looks so useful! But unfortunately this diagram, which was created in the 1940s, is incorrect and has no real numbers behind it.ref In reality “nutrients interact and different plants respond differently to a change in pH” as described above so there is no one-size-fits-all diagram.ref

While I’m in mythbusting mode, there isn’t any such thing as ‘soil pH’ either! As noted in this excellent study from March 2023, pH can only be measured in a liquid. Unless you are over-watering, it’s likely your soil is not a liquid, therefore the soil itself does not have a pH. The pH that is being measured when ‘soil pH’ is measured is actually the pH when the soil is mixed with water – whilst this is indicative of the pH that might be present on individual soil particles, there is probably a range of pH instead across different particles. The pH of the water on a soil particle and the pH of the water on a root hair combine to create the true pH environment for a particular nutrient on a particular root. This is obviously not very easy to measure! See the end of this article for my bonsai media pH experiment.

The study mentioned above basically claims that most studies on pH and soils have failed to take into account the interplay between availability in the soil and plant uptake of a nutrient, which often work in opposite directions and so pH should not be taken to be the main factor in nutrient uptake except in specific circumstances. But looking at all of the above, it does seem like slightly acidic conditions should optimise all of the different reactions taking place – between 6 and 7 pH.

To bring it back to my bonsai, in my London garden with hard tap water of pH near 8, on the surface it would appear that this has the potential to cause a phosphorus deficiency in my plants, and perhaps affect their boron, molybdenum and metallic ion levels (we care about magnesium particularly which is used for photosynthesis – magnesium uptake increases at high pH but availability in the soil decreases).

But tap water is not the only thing affecting pH in the water in my bonsai soil. It’s also affected by the pH of my rainwater, which was 5.89 on the last measurementref, as well as the medium in my pots. I use composted bark, biochar and molar clay. Composted bark has organic components so is acidic, biochar is slightly alkaline and molar clay appears to be acidic – and this pH will become evident when particles of these components dissolve into the water. So the actual pH of the solution in my bonsai soil is anyone’s guess! All I can conclude from this is that a long summer without rain might cause my soil to increase in pH due to the removal of one acidic component – the rainwater.

The other thing to consider is that you can obviously adjust the availability of nutrients by adding them to your soil. So even if uptake is reduced by a particular pH, making more nutrients available could compensate for this. Hence the importance of regular fertilising for our bonsai, and using a range of different fertilisers which provide different nutrients.

Finally if you want to test the pH of your bonsai medium, a good approximation can be made by using a red cabbage and some distilled water (don’t use tap water, as this will affect the outcome if it’s not neutral to start with). Simply boil up a bit of red cabbage in (distilled) water, let it cool and while you are doing that put a representative piece of your bonsai medium into some water (also distilled). Allow them to soak for a while. Remove the cabbage from the cabbage water, strain the medium out of the bonsai medium water, and pour some of the cabbage water into the bonsai medium water. It should change colour according to the pH as follows (you can read more instructions here):

I performed this experiment on different bonsai mediums I had sitting around in my shed by soaking them in filtered water for 1 hour, then adding the cabbage indicator. The results were interesting! I was expecting the Kanuma to be acidic but it was actually neutral, as was my bonsai mix (which included some molar clay, bark, biochar, pumice and compost), and the pumice was surprisingly slightly alkaline. A rather small amount of biochar caused the indicator to go dark blue, which definitely tells me it needs to be used in moderation (although other mechanisms in biochar make nutrients available to plants, which you can read about in my biochar post).

What I conclude from all this is that my use of composted pine bark in my bonsai mix is probably a good thing as it will counteract the alkalinity from the tap water. This was a suggestion I learned from Harry Harrington’s website – although he recommends it for water retention, it would appear to balance a high pH medium or water as well. It also has the added benefit of being organic matter, which is a fertiliser in itself, creating more nutrient availability even if the calcium carbonate in my water locks some away. The need for applying fertiliser regularly is also apparent, as you just don’t know how nutrients are behaving in your particular bonsai soil and you need to give each tree every chance they have to access the nutrients they need. But overall other than causing annoying limescale marks on pots, my bonsai seem completely fine with hard water.

About Water hardness, pH and bonsai.

I’m using tap water to water my bonsais, however the pH is around 8 due to carbonate salts

In order to get a more suitable pH for fertilizing I decided to decrease the pH to 6.5 by adding posphoric acid.

In your opinion decreasing the pH is a good practise for this purpouse ?

Thank you