Another epic topic which has occupied scientists for the best part of 400 years, the equation for photosynthesis itself was not understood until the 1930s.ref

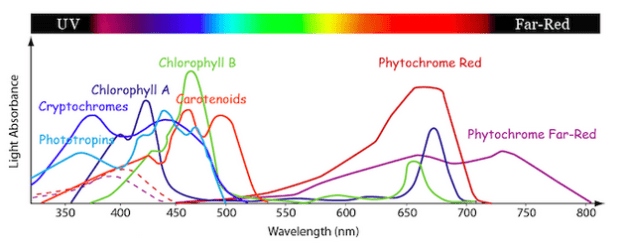

Photosynthesis is the process of turning energy from sunlight into chemical energy, a process which famously is performed by plants, specifically by plant cells containing ‘chloroplasts’. Chloroplasts contain a substance called chlorophyll. Chlorophyll is often described as a ‘pigment’ – but this makes it sound like its only role is to colour things green! Which of course it isn’t – being green is just a result of its real function which is to absorb sunlight of a certain spectrum. Chlorophyll absorbs visible light in two regions, a blue band at around 430 nanometers and a red band around 680 – according to Vogel. Other sources state the bands are 680 nm and 700 nmref. Everything else is reflected, which looks green. Chloroplasts are believed to have originally been cyanobacteria which were incorporated into plant cells to provide photosynthetic capability (Lane, 2005). To see where chloroplasts and chlorophyll are present within a leaf, check out this post on leaf structure.

The sequence of reactions which happen during photosynthesis are known as the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle, after the scientists who discovered it. The simplified equation describing photosynthesis is as follows:

6CO2 + 6H2O –light energy–> C6H12O6 + 6O2.

This suggests that photosynthesis is the exact opposite of respiration, creating glucose instead of consuming it. But actually this equation is incorrect as photosynthesis does not create glucose. The Calvin et al cycle produces a molecule called G3P which is a 3 carbon sugar which can be used to create other molecules. Anyway, that’s probably not super-relevant for bonsai! The main insight from the equation above is that light energy is needed for plant survival and growth – this is why trees do not like being inside unless they have a suitable artificial light source.

Another point to note is that plant cells, like all living cells, respire. Plant cell respiration is like animal respiration, that is, cells consume oxygen and glucose to produce energy, while emitting carbon dioxide and water. Cells use respiration to generate the energy they need for metabolism (basically, keeping the cell alive and functioning). All cells in a tree respire, including the leaves, roots and stems, 24 hours a day. This means trees offset some of their photosynthesis by respiring – in particular at night when no photosynthesis occurs.

On balance, leaves produce a lot more sugars and oxygen through photosynthesis than they use during respiration – and this provides the energy they need to maintain themselves and grow. In fact the point at which they *don’t* produce more than they use through respiration is as low as 1% of full sunlight (Vogel). Note that this low level can be reached if a leaf is entirely shaded by 2 other leaves, since the typical light transmission through a leaf is only 5%.

Another interesting fact about photosynthesis is that leaves can only use about 20% of full sunlight before the photosynthetic system saturates (Vogel). This number actually varies depending on the species and leaf type. So leaves below the top layer (likely to be ‘shade leaves’ described in this post: Leaves) can still get enough light from partial exposure, if they are slightly shaded or lit for only part of the day, to saturate and max out their photosynthetic capability. The majority (99%) of the energy absorbed is used to maintain the leaf itself, so only 1% is released for growth.

But – back to the photosynthesis equation – which is an extremely simplified version of what is actually happening. Photosynthesis requires 150 discrete steps involving a similar number of genesref. A good reference is this Nature article.

Photosynthesis takes place in two stages. First the ‘light dependent’ reactions happen. Light energizes electrons within the chlorophyll, and these electrons are harnessed to produce ATP (adenosine triphosphate) and NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate) which are molecules used by cells for energy and as an electron source. The chlorophyll replaces its lost electrons by taking some from water – effectively they ‘burn’ or oxidise water, leaving the oxygen behind as a waste product (Al-Khalili).

After this the ‘light independent’ reactions happen. These are facilitated (sped up) by an enzyme known as RuBisCO. Using the energy sources created in the first step (ATP and NADPH), RuBisCO ‘bolts’ together the hydrogen from the water, and the carbon and oxygens atom from the carbon dioxide, along with phosphorus, to make the 3 carbon sugar glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate (C3H7O7P) (Lane, 2005). This is known as carbon fixation.

In reality there is also a third stage where the ingredients for the cycle are regenerated so that it can continue running.

The full equation (the Calvin-Benson-Bassham cycle) – is:

3 CO2 + 6 NADPH + 6 H+ + 9 ATP + 5 H2O → C3H7O7P + 6 NADP+ + 9 ADP + 8 Pi

(Pi = inorganic phosphate, C3H7O7P = glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate or G3P)

Sorry for geeking out for a minute there!

An important point is that photosynthesis doesn’t just go up with increasing sunlight, it has a set of limiting factors which were described by Blackman in 1905 in his articleref “Optima and Limiting Factors”. He said “When a process is conditioned as to its rapidity by a number of separate factors, the rate of the process is limited by the pace of the slowest”. The limiting factors he described for photosynthesis included light intensity, carbon dioxide and water availability, the amount of chlorophyll and the temperature in the chloroplast.

The amount of sun needed to max out photosynthesis from a light intensity point of view is not as high as you would imagine. Vogel says a leaf “absorbs about 1000W per square metre from an overhead sun shining through a clear sky” and photosynthesis only consumes 5% of this – 50W per square metre. Obviously this is going to vary depending on the species and whether a leaf is a sun leaf or a shade leaf.

But what does it mean for bonsai? Well – you might have spotted some other elements in the photosynthesis equation. NADPH (formula C21H29N7O17P3) contains nitrogen and phosphorus, as does ATP (formula C10H16N5O13P3). RuBisCO relies on a magnesium ion to perform its role as a catalyst. There are a bunch of other enzymes and co-factors which are required to support photosynthetic reactions as well – which explains why certain nutrients (including Nitrogen, Phosphorus, Magnesium, Potassium, Chlorine, Copper, Manganese and Zinc) are critical for trees in varying amounts – more here: Nutrients for Trees.

And if you’re concerned about whether your trees have enough light for photosynthesis, you can see exactly how much energy is arriving on your outside bonsai at this site. Find your location and download the PDF report and you’ll see the irradiation levels – which can be useful in understanding how your bonsai trees will fare. As an example, the max in my location is 328Wh/m2 in April which explains why the olive trees in London are so unhappy looking – if you look at irradiance in Greece, where they thrive, it barely ever goes under 328Wh/m2 even in winter! Trees in Greece receive nearly double the amount of irradiance than those in South West London.

One final point of interest with admittedly little relevance to bonsai – some plants (nineteen different plant families, independently of each other) evolved an improved photosynthetic process which is known as C4 photosynthesis. This concentrates CO2 nearer to the RuBisCO enzyme, reducing its error rate. Unfortunately most trees use C3 photosynthesis with its associated inefficiency – other than Euphorbia, which are apparently “exceptional in how they have circumvented every potential barrier to the rare C4 tree lifeform”ref.