Understanding the exact role of individual plant nutrients is actually quite complicated. This is because many nutrients have multiple roles, and research hasn’t always clearly identified each role. It’s also because nutrients don’t act on their own – they usually form part of a larger molecule, such as an enzyme, and they usually interact with other nutrients, molecules and environmental factors such as pH. Then it requires diving deep to the molecular level to work out how chemical reactions take place and even how individual electrons move in the presence of the enzyme. I’ve read a bunch of papers and articles about the nutrients below but there is sure to be more out there – consider this a taster.

Macronutrients

Macronutrients are those inputs which plants require in substantial volumes in order to grow and metabolise. There are six macronutrients, of which three are metals.

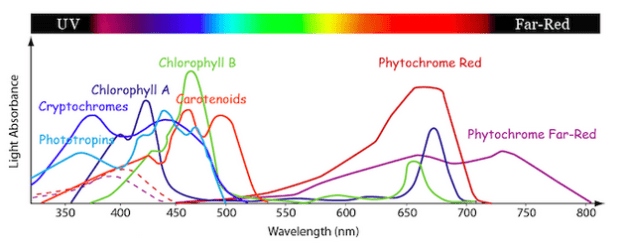

1. Nitrogen: nitrogen is needed by plants for various reasons but one of the most important is for photosynthesis. Nitrogen is a component of chlorophyll, the green pigment in leaves which absorbs the energy from sunlight to break apart water in the photosynthesis reaction. The chemical formula of chlorophyll is C₅₅H₇₂O₅N₄Mg – as you can see both nitrogen and magnesium are needed in addition to carbon, hydrogen and oxygen which is obtained from air and water.

Secondly, nitrogen is a key component of amino acids, which are used in all living things to make proteins. There are 21 amino acids in plants which are connected together in a myriad of different sequences and shapes to make the different proteins. Examples of plant proteins include the storage material in seeds and tubers, plant cell membranes and the enzyme known as RuBisCO. RuBisCO is present in leaf cells alongside chlorophyll, and enables carbon fixation during photosynthesis – it is said to be the most abundant protein on Earth and represents 20-30% of total leaf nitrogenref. So photosynthesis requires chlorophyll and RuBisCO, both of which rely on nitrogen as a component element.

Finally nitrogen is present in the four bases used to create DNA (adenine, thymine, guanine & cytosine) and RNA (adenine, urasil, guanine & cytosine) which enables cell replicationref.

Nitrogen needs to be in soluble form to be used by plants, either as nitrate or ammonium, which requires the presence of specific bacteria either in the soil or in the plant’s roots. As I mentioned in my first post about nutrients, Hallé states that obtaining nitrogen is a constant challenge for plants. This is why the fertiliser industry is so prosperous – but unfortunately also so damaging for the environment. The Haber-Bosch process used to make Ammonia (NH3) is “one of the largest global energy consumers and greenhouse gas emitters, responsible for 1.2% of the global anthropogenic CO2 emissions”ref and nitrate runoff from highly fertilised fields damages rivers and ecosystems.ref The natural world has some clever ways to make nitrogen accessible – some plants incorporate bacteria into their roots which can do this, and in old growth Douglas fir forests, lichen in the canopy which contain cyanobacteria capture nitrogen from the atmosphere and when they fall to the forest floor they rot into components which trees can access (Preston, ‘The Wild Trees’). Similarly a relatively sustainable source of nitrogen for plants is rotting organic matter (along with the necessary microbes) – compost and manure are good options.

2. Phosphorus is needed in plants – and in fact in most living things – because it’s a key component of the molecule used to store, transport and release energy in cells. That molecule is called adenosine triphosphate (“ATP”) and it’s created during photosynthesis by adding a phosphorus atom to adenosine diphosphate. The ATP can then be transported throughout the organism to be used where energy is required, at which point it’s converted to ADP (adenosine diphosphate) which releases energy back to the cell. Phosphorus also provides the structural support for DNA and RNA molecules, needed for cell replication.

For plants phosphorus is fundamental to photosynthesis, as a phosphorus-containing substance called RuBP (C5H12O11P2) is used to regulate the action of RuBisCO in fixing carbon from carbon dioxide.

Phosphorus is a key part of most fertilizers and manure is a good sourceref.

3. Sulphur is a constituent of two amino acids – methionine and cysteine. Cysteine is used to create methionine as well as glutathione, an anti-oxidant which helps plants defend themselves against environmental stressref. Methionine is involved in cell metabolism and the majority of its use in the cell is to synthesise ‘AdoMet’ which is used in methylation reactions (such as DNA methylation which regulates gene expression) and to create the plant growth regulator ethyleneref.

Manure is a source of sulphur for plants.

Metals

In addition to the top three outlined above, it turns out that plants need some atoms of various metals as well. In order to understand why, we need to know that plant cells are full of chemical reactions which perform all the different functions required for metabolism. Helping these chemical reactions along are a type of protein known as enzymes. Enzymes act as a catalyst to chemical reactions in cells, speeding them up without consuming the enzyme material itself. Some enzymes have metal ions at their heart which assist the reaction (called ‘co-factors’) and these play a critical role in the enzyme’s function (for example magnesium is used in RuBisCO).

Three of the six macronutrients needed by plants are metals – potassium, calcium and magnesium.

4. Potassium is one of the three major macronutrients usually found in NPK garden fertilisers (K is the chemical symbol for potassium), reflecting its important role across several different dimensions of plant growth. One important role is in the production of proteins. As outlined above, proteins make up a large part of plant biomass, and the key protein RuBisCO is necessary for photosynthesis. Proteins are manufactured on structures called ribosomes within the cell – and ribosomes need potassium in order to do their jobref.

The other important role for potassium is in providing the pressure within plant cells which keep them stiff and ‘turgid’ – without it they would become flaccid and the plant would fall over. The manipulation of turgidity within leaves is one way a plant controls the level of air coming into the leaf – to close off the air holes (stomata) the guard cells around the stomata are made more turgid which closes the gap between them. Potassium is involved in this process.

In nature the main source of potassium is the weathering of rocks, but it’s also contained in organic matter, particularly in seaweed.

5. Magnesium is a component of the chlorophyll molecule and is key to the operation of RuBisCO, both of which enable photosynthesis. It is found in soil from the weathering of magnesium-containing minerals – the University of Minnesota recommends dolomitic limestone or tap waterref.

6. Calcium isn’t just used for human skeletons, it’s also used for plant structure as it strengthens the cell walls in plants. Its presence (or absence) is also used for signalling of stresses to the plant, allowing it to activate defences against pathogens. Sources of calcium for gardening include lime or shells.ref

Micronutrients

Micronutrients are required in much smaller amounts than macronutrients, although they are still required.

7. Boron appears to have been identified as a plant micronutrient mainly due to the effects of not having enough of it, with researchers having observed that boron deficiency leads to root, leaf, flower, and meristem defects. The precise role that boron plays is not easy to find in the literature, other than it being generally agreed to be important as a structural component of the plant cell wall, helping to provide rigidityref. Boron also appears to be required for reproduction, and a lack of it can affect pollen germination, flowering and fruiting. Because boron has poor mobility in a plant and cannot be moved from one part of the plant to another, continued exposure to it is needed in order to avoid a deficiency – but the exact levels vary widely by plant.

Sources of boron include borax (sodium borate) but since boron toxicity is apparently possible at high levels be very careful with this approach. Obtaining boron from organic matter or liquid seaweed instead may be less risky.

8. Chlorine was added to the plant micronutrient list in 1946 since it was found that chlorine molecules are required as part of the machinery of photosynthesis – particularly relating to the water-splitting system. In addition to this essential function, chlorine has also been found to be beneficial at macronutrient levels, enabling “increased fresh and dry biomass, greater leaf expansion, increased elongation of leaf and root cells”ref.

Since most people will be using tap water for watering their bonsai, getting adequate chlorine to your trees should not be a problem, but if you are using rainwater perhaps consider tap water every now and then.

9. Copper is essential for plants because along with iron it makes up part of an enzyme called cytochrome oxidase which performs the last of a sequence of steps in respirationref. Cytochrome oxidase is present in the mitochondria of plant cells – these are separate organelles with their own unique DNA which are dedicated to energy production. Copper is also found in plastocyanin, a protein which is responsible for electron transfer in the thykaloid – the light-dependent part of the chloroplastref. This protein is key to the conversion of light energy to chemical energy in the cell during photosynthesis. Copper is found in the soil but apparently is deficient in soils with high amounts of organic matterref.

10. Iron is present in a large number of different enzymes within plant cells, appearing in chloroplasts (where photosynthesis takes place), mitochondria (where energy is created) and the cell compartment. Iron is therefore a key nutrient for growth and survival in plants – in just the same way it is with humans and other forms of life. Iron is a component of so many enzymes that there is a specific name for them – ‘FeRE’ or iron requiring enzymes (Fe is the chemical symbol for iron).

Iron can be toxic if too much is present, so plants have evolved mechanisms to remove it when it gets too high. ref1 ref2 ref3

11. Manganese is also a co-factor to enzymes involved in photosynthesis, as part of the ‘oxygen-evolving complex’ in photosystem II, which contains 4 manganese ions. Photosystem II “is the part of the photosynthetic apparatus that uses light energy to split water releasing oxygen, protons and electrons”ref.

12. Molybdenum is used by certain enzymes to carry out redox reactions (reactions where electrons are gained or lost from a molecule); these include nitrate reductase, xanthine dehydrogenase, aldehyde oxidase and sulfite oxidaseref. Its role facilitating the nitrogen pathway in a plant is important since nitrogen is the nutrient plants require the most of, and the presence (or absence) of molybdenum can make a big difference to the efficiency of nitrogen uptake which in turn affects growth rates and plant health.

13. Nickel is a co-factor to the enzyme urease which breaks down potentially toxic urea (a product of metabolism) into ammonia which can then be used as a source of nitrogen for the plantref.

14. Zinc is the final micronutrient alphabetically but not in terms of importance. It is associated with 10% of all proteins in eukaryotic cells including those of plants, assisting as a co-factor to many enzymes and so enabling many different biological processes including transcription, translation, photosynthesis, and the metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Zinc also plays a role in ensuring the correct folding pattern for proteins as they are created.ref

Interestingly, zinc deficiency is associated with smaller leaves and internodes, which you might consider a benefit for bonsai, but perhaps not at the expense of your trees’ core biological processes!

Wait – I only got to 14 and there are supposed to be 17 – what the heck? Oh yeah – here they are (15) carbon and (16) oxygen from carbon dioxide, and (17) hydrogen from water (H2O). Did you know that the oxygen emitted from plant photosynthesis actually comes from the water and not from the carbon dioxide? More in Photosynthesis.